- Diane Murray

Tealeda Nesbitt,

Kristine Rodriguez

Bryan Rosen

MSTU 4039.001

Dr. Joey Lee

Table of Contents:

About the game 3

Rules 4

Process document 6

Educational Theory 10

With a focus on reducing waste, conserving energy, and shopping smart, Serious Waste Race is an educational game that connects players’ daily actions/choices to their overall environmental impact. Players’ race through a 24-hour day, making different choices that positively or negatively impact the environment. Careful– you can’t continue with your day if you cause too much damage to the environment! Be the first player to get through the day while causing the least amount of damage to the environment and you WIN.

While the actions/choices each player makes in Serious Waste Race are influences by luck, this game aims to start conversations about the environmental impact of players’ daily actions/choices and empower them to take control of their actions in real-life.

RULES:

Included in the Game:

1 board, 4 environmental impact cards, 30 leaves, 4 tokens (each a different mode of transportation), 1 dice, 4 sets of actions/choices cards (morning, afternoon, evening, & night), and questions cards.

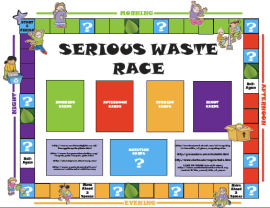

About the Board:

The board has four types of squares: text squares, leaf squares, trivia squares, and action squares. All text squares have instructions written on them. All leaf squares have the image of a leaf on them. All trivia squares have a large blue question mark on them. All action squares are a solid color. The color of each action square corresponds to the time of day for each side of the board. Each side of the board represents a different time of day: morning, afternoon, evening, and night. These colors also correspond to the different actions/choices cards for the same time of day. For example, the color red represents afternoon. Red is used on afternoon actions/choices cards and on afternoon trivia squares.

How to Win:

The first player to make it through the day (all the way around the board and back to the start/finish square) must answer a questions card: a correct answer will WIN the game! If the player answers the question incorrectly, the player will have to wait for his/her next turn to try another question card. (Players do not need to roll exactly to the last square as long as their roll would put their token on or beyond the start/finish square).

Environmental Impact Cards:

Each player starts with 6 leaves on their environmental impact card. This card represents the impact the player’s actions/choices have on the environment. If a player loses all the leaves from their environmental impact card, the player must RESTART the day (move the player’s token back to the start square and reset the environmental impact card).

Modes of Transportation:

Each token represents a different mode of transportation: car, subway, bike, & on foot. Each mode of transportation has a different environmental impact and, therefore, influences the game in different ways. As a penalty, each mode of transportation will move backwards a certain number of spaces:

Game Setup:

During a Player’s Turn:

**Return all cards to the bottom of their stack once they have been read.

Process Document:

![]() As soon as the project was assigned, the members of Playgroup 1 decided that each on of us would come up with 3-4 game ideas and share them in a google document. We would then discuss our ideas and decide as a group which game concept to develop. We held a conference call meeting over Halloween weekend and agreed to develop a recycling game. The game would have an educational aim to teach players about waste, managing waste, and how daily actions impact the environment. The conference call ended with an assignment: for each of us to think about the core metrics of the recycling game. We scheduled a meeting before class on the following Monday (11/2). In that meeting, we narrowed our target audience to middle-school children. Kristine came to the 2pm meeting with a game idea semi-fleshed out with pencil, paper, and post-its (image below). As a group, we discussed the basic educational concepts we want to convey and began developing the game.

As soon as the project was assigned, the members of Playgroup 1 decided that each on of us would come up with 3-4 game ideas and share them in a google document. We would then discuss our ideas and decide as a group which game concept to develop. We held a conference call meeting over Halloween weekend and agreed to develop a recycling game. The game would have an educational aim to teach players about waste, managing waste, and how daily actions impact the environment. The conference call ended with an assignment: for each of us to think about the core metrics of the recycling game. We scheduled a meeting before class on the following Monday (11/2). In that meeting, we narrowed our target audience to middle-school children. Kristine came to the 2pm meeting with a game idea semi-fleshed out with pencil, paper, and post-its (image below). As a group, we discussed the basic educational concepts we want to convey and began developing the game.

Version 1.0: Just Use Less.

Kristine’s inspiration for the game was a video from the Media That Matters Film Festival entitled The Secret Life of Paper. Her game involved a large board where you start with 6 pieces of recyclable and non-recyclable trash at the bottom of the page (indicated by the blue and pink pieces of paper). At each turn, the player would decide what to do with 3 pieces of trash while 6 new piece of trash would be added to the board. Options for trash placement included adding the trash to a compost section, recycle bins section, or a landfill section. When an item was recycled, an orange piece of paper would show up at the top of the board to indicate that there was pollution involved in recycling (a consequence to consider). The game ended after 20 turns. If the player survived 20 turns (without the board being filled completely with trash) they ‘won.’ We thought through many of the items that we could add to this game and what they might look like: plastic cartons, ketchup packets, parts of burger buns, band-aids, plastic bags, etc. We expanded our google document to track our ideas. We named the game: Just Use Less based on a line in the above mentioned video.

![]() However, when we play-tested Just Use Less, we found some problems. First, we could think of way involve multiple players. Second, manage the addition and subtraction of the recyclable/non-recyclable items became very confusing. Third, the game’s message wasn’t clear. It seemed to be more about learning the rules of recycling and less about understanding the problem of waste and waste management. Plus, it just wasn’t fun to play. The game needed to change.

However, when we play-tested Just Use Less, we found some problems. First, we could think of way involve multiple players. Second, manage the addition and subtraction of the recyclable/non-recyclable items became very confusing. Third, the game’s message wasn’t clear. It seemed to be more about learning the rules of recycling and less about understanding the problem of waste and waste management. Plus, it just wasn’t fun to play. The game needed to change.

Version 1.2: Just Use Less—a card game?

Bryan suggested taking the cards from the initial version of the game to create a 2-player card game (image at right). However, even with the card game, gameplay continued to be detached from game’s goals. It was too simplistic to be fun. We left class that day worried about the future of our recycle game, but determined to make it better. We spoke about the educational goals of the game and decided to each think of how to improve/change the game to meet our educational goal. We planned to meet again on Friday 11/6. We continued to use our google document as a space to post new game ideas: Go Recycle (like Go Fish), Recycle Uno, and others.

By Friday 11/6, we had 2 solid game ideas to play test. Both games were built with paper and pen. In this process document, these games are titled Version 2.0 and Version 3.0.

![]() Diane expanded our original recycling board game to develop Version 2.0. She created a 2-player game where each player had a house, created waste, and decided whether to place the waste in the compost, appropriate recycling container (paper, glass, aluminum), or landfill. She brought written rules, cards, and a board to play test (images at right & below). Diane had solved many of the issues that we had with our first game. However, by play testing Version 2.0, we discovered that the rules were very difficult to follow. It was confusing to figure out what each player could do on their turn and when the turn ended. Players weren’t clear when they should pick up a “Clear Compost” card or a “Reason to Recycle” card. Although, the game allowed players more freedom to redistribute resources, it still didn’t have the strong teaching element we wanted. The focus of the game was still being reduced to simple rules of recycling. It didn’t necessarily teach about individuals’ daily impact on the environment. We realized that we wanted a game that relates back to the middle school students’ every day live. And we wanted to pushed beyond a simple review of recycling rules.

Diane expanded our original recycling board game to develop Version 2.0. She created a 2-player game where each player had a house, created waste, and decided whether to place the waste in the compost, appropriate recycling container (paper, glass, aluminum), or landfill. She brought written rules, cards, and a board to play test (images at right & below). Diane had solved many of the issues that we had with our first game. However, by play testing Version 2.0, we discovered that the rules were very difficult to follow. It was confusing to figure out what each player could do on their turn and when the turn ended. Players weren’t clear when they should pick up a “Clear Compost” card or a “Reason to Recycle” card. Although, the game allowed players more freedom to redistribute resources, it still didn’t have the strong teaching element we wanted. The focus of the game was still being reduced to simple rules of recycling. It didn’t necessarily teach about individuals’ daily impact on the environment. We realized that we wanted a game that relates back to the middle school students’ every day live. And we wanted to pushed beyond a simple review of recycling rules.

![]() Kristine had developed a game idea that focused on actions in a 24-hour day. Based on recent work with middle school children, she wanted to add a “hangman-like” element that focused on the consequences of bad environmental choices. As a group, we created a board that was broken into 4 phases of the day: morning, afternoon, evening and night. There were corresponding cards that related to each time of day with good or bad actions written on them. In Version 3.0, players choose a game piece and race around the board, picking up action “chance” cards that caused them to lose leaves from “hangman-like” tree cards. We decided to add ‘did you know’ information to the action cards. We also added trivia spaces and cards. Tealeda suggested that the tree cards should be reusable, with leaves attaching by Velcro.

Kristine had developed a game idea that focused on actions in a 24-hour day. Based on recent work with middle school children, she wanted to add a “hangman-like” element that focused on the consequences of bad environmental choices. As a group, we created a board that was broken into 4 phases of the day: morning, afternoon, evening and night. There were corresponding cards that related to each time of day with good or bad actions written on them. In Version 3.0, players choose a game piece and race around the board, picking up action “chance” cards that caused them to lose leaves from “hangman-like” tree cards. We decided to add ‘did you know’ information to the action cards. We also added trivia spaces and cards. Tealeda suggested that the tree cards should be reusable, with leaves attaching by Velcro.

At the end of our 2-hour session, we had played and discussed Version 2.0 and Version 3.0. The rules of Version 3.0 were straight-forward and understandable. The game also seemed better able to deliver the more complex message we were striving for: wasteful everyday decisions have real environmental consequences. The game could easily be related to middle school students’ everyday lives. Gameplay of Version 3.0 was fun and engaging. We thought it would be an easier game to play-test with a larger group. We decided on Version 3.0 because it was easier to explain, had the ability to incorporate multiple players, and was a better match our educational goals.

After deciding to continue to develop Just Use Less Version 3.0, we split up the tasks for create each portion of the game. We wanted a clean version for play-testing on 11/9. We met an hour before class on 11/9 and play-tested the game ourselves before the rest of the class arrived. Although we had few changes after play-testing our own game, having classmates play-test the game was extremely productive. There were some elements missing that we didn’t realize until our classmates played the game.

We learned that the game wasn’t challenging enough. Players liked the environmental impact cards (trees) and the adding/subtracting leaves element. However, there need to be more or different positive/negative consequences for answering questions. The format of the question cards needed to change. We got helpful feedback that let us rethink important elements, including:

Version 3.1: Serious Waste Race

Again, we met as a group to play-test our game before class on 11/16. We were excited by the way our changes had improved the game. Again we received unexpected feedback from classmates and were pushed to make important changes. Players reported feeling that their choices had no impact within the game. We decided to change the game tokens so they were not treated equally. Instead of rolling the dice and having the same consequences, the player would choose to play the game as a car, subway, bike, or pedestrian. Each of these pieces had different consequences in the game. A player could choose to be the car, which would move them forward at a rapid rate, but large environmental impact penalties would result for bad actions/choices. We play tested the game again on Tuesday 11/17 and tried multiple new scenarios. The rules changed multiple times as we tried to find the best rules. The game became too predictable without the mechanic of rolling the dice. Adding that back to the game, we tried different pairs of reward/penalties. Examples from our notes include: “roll the dice, land on an action square – receive a good card: stay put, receive a bad card: move back according to the type of play-piece you are AND you lose a leaf,” and “land on a question card and answer it correctly, you gain a leaf. If you answer the question wrong, you lose a number of leaves depending on if you are a car (3), subway (2), bike (1), on foot (1).” We removed the element of stealing leaves from other players, although this had been a suggestion by a classmate in the first class play-test. We agreed with another classmate that it didn’t fit the message of the game. Finally, we added leaf squares that act as teleports to other leaf squares.

Version 3.2: Serious Waste Race

We took feedback from classmates, play-tested many scenarios, and created what we think will be an excellent game. It is important that players view this game as about more than just recycling. We strived to create a game that connected daily actions to environmental consequences. While selecting good/bad action cards is governed by chance, we feel this mimics how some of these actions are done without thinking during daily life. Actions, even those done without thought, still have an impact. If players are frustrated by this, we hope it causes them to consider taking control of their actions in real life. Likewise, we enjoy the rule of restarting the game if the environmental impact card loses all the leaves—you do enough damage to the world and you can’t go on with your day. We’ve see how this element bumps players out of the race and although sometimes frustrating, we believe it drives home an important lesson. Also, we are very happy with the addition of different token types. By adding the tokens as modes of transportations and assigning them different consequences, we’ve allowed players to demonstrate learning by strategizing which token to select and play.

To close our process document, we’d like to include shots of the evolving game board (ending with the final game board). Marquina continued to develop the game board during the design process and was meticulous at documenting changes throughout the project.

Educational Theory:

Conceived as an educational game with a social activist agenda, the development of Serious Waste Race, a non-digital game, was grounded in educational theory. Targeting middle school students, Serious Waste Race aims to raise players’ awareness about the impact/consequences of daily actions on the environmental. When added together, the often ignored, rushed, and unthought-of actions of individuals, such as leaving the water running when brushing teeth or leaving chargers plugged in, has tremendous environmental impact. Drawing attention to the waste caused by these daily actions, Serious Waste Race aims to start conversations about environmental impact in a creative, engaging, and fun learning environment: a game. The following paper explores several key educational theories that were instrumental during game design. In closing, this paper offers real world suggestions for how to improve the educational success of this game, highlighting both strengths and weaknesses of the game design.

Knowledge and play

A result of experience and application, a constructivist view of teaching is dynamic (Olsen, 1999). Knowledge learned is based on observation and concrete interaction with the senses, logic, and reasoning. Thus, learning becomes the process of activating prior knowledge through experimentation, observation, and abstraction. The teacher’s role is to ask the right questions and develop tasks that allow student to recover previous knowledge. Serious Waste Race attempts to activate student’s prior knowledge by connecting familiar daily actions with environmental impact. Students can reflect on their own daily actions and, through observation and abstraction, determine if their actions are wasteful.

With each actions/choices card, students have equal opportunity to be present with positive or negative environmental scenario involving the same action. They therefore have a model of ways to potential improve wasteful behavior. Although not explicitly stated in the game rules, it is the designers’ intention that students will see the opposite nature of the action cards and discuss the actions in the cards among themselves. Through these observations and discussions, there is potential for students to consider positive courses of action in their own life. As describe later in this paper, we believe the educational potential of Serious Waste Race will be more successful when these types of discussions are scaffold by a teacher. Without scaffolding, we believe the positive and negative consequences built into the game (such as wasteful actions causing the loss of leaves and making it more difficult to succeed in the game) will reinforce connections and help the student become more aware of how to make better environmental choices.

It is the game designers’ intention that the loss and gain of leaves adds drama to gameplay. Drama is an important quality of many great games. Drama makes games fun to play and motivates people to become players of a game. Marc LeBlanc discusses the importance of drama in games in his essay Tools for Creating Dramatic Game Dynamics (2007). A game’s emotional content and the kinds of fun players have when playing are the aesthetics of a game. LeBlanc’s defines an “aesthetic model for drama in terms of dramatic tension, the intensity of the struggle, and dramatic structure, the way that intensity changes over time” (p. 458). Dramatic structure is a key component of a good game and dramatic tension should be building towards the end of a game. Uncertainty and inevitability are two factors in combination that control the dramatic tension of a game.

Serious Waste Race has a number of different mechanics and rules that make the game dramatic and impact the dynamics and aesthetics when playing the game. The leaf spaces on the board, the consequences associated with each of the game pieces, and the environmental impact cards are some of the key mechanics that influence the dramatic tension and structure of the game. The green leaf spaces on the board allow players to take a big lead or catch up to other players by automatically moving the player ahead to the next green leaf space on the board. Also, the different consequences associated with each of the tokens in the game greatly affect the game’s dramatic. The dramatic tension can climax near the conclusion of the game considering the suspenseful nature of races. Adding to that, uncertainty in the form of luck and inevitability in watching leaves dwindle in number builds mini-climaxes of dramatic tension throughout the game— players who lose all their leaves need to start over from the beginning.

In James Paul Gee essay Good Video Games and Good Learning, Gee focuses on learning principles in the context of video games. Although Serious Waste Race is a non-digital game, many of the principles Gee discusses can also be applied. For example identity and situated meanings are two learning principles that can be connected to Serious Waste Race. All of the action cards begin with the pronoun “you” followed by a negative or positive action. Although students may or may not actual perform the action as outline on the card in real life, they can identify with the pronoun “you” (this is similar in the game of Life). Games capture players through connections with identity. Players will act and learn through their commitment to a new identity in games (Gee, 2007).

Situated meanings concerns how people better learn words and facts when they can connect them to experiences and understand their contexts (Gee, 2007). In Serious Waste Race, players learn the situated meanings of actions on the choice cards through the consequences of the card and the “did you know” facts. It was the gamer designers’ intention to choose true, yet shocking statistics for the “did you know” facts. Gee states, “games always situate the meanings of words in terms of actions, images, and dialogues they relate to… They don’t just offer words for words” (Gee, 2007).

Finally, fun games help students relax and allow them to participate without the fear of answering incorrectly. Using fun to help students learn is always a great tool. Raph Koster states in his book A Theory of Fun for Game Design, that games give students other ways to learn a topic rather than the typical practices, such as lecture (Koster, 2005). Particularly because the topic of environmental awareness seems to be everywhere these days (yet people rarely change their habits), the designers of Serious Waste Race wanted to create a new way to address this issue. Serious Waste Race strives to connect the concepts of personal behavior and environmental impact in a fun, unique way.

Real world circumstances

As mentioned above, it is the opinion of the game developers that Serious Waste Race would be most educationally successful when used as a classroom activity. While it is believed that target players (middle school students) would engage in the similar types of experimentation, observation, conversation outside of the classroom, we feel having a teacher scaffold the activity would lead to better educational outcomes.

In making this suggestion, the designers of this game acknowledge some repetitive elements of the game that may reduce motivation to continue playing outside of the classroom. Namely, picking up cards and reading information aloud. Some of the cards (question and action cards) are text heavy and reading aloud becomes dull (for readers and listeners). It is important that the information on the cards be shared with all players. Perhaps as part of a classroom activity, students would remain more motivated to continue reading aloud. Likewise, Serious Waste Race relies heavily on chance/luck to determine the course of action within the game. As an attempt to make player’s decision-making a more relevant factor in the game, player token selection was made more consequential in the game’s overall dynamics. The game designers felt that the role of chance/luck within the game mimics how some of the highlighted actions are done without thinking during daily life. Actions, even those done without thought, still have an environmental impact. If players are frustrated by chance/luck element, the game designers hope it causes them to consider taking control of their actions in real life.

Although the educational success of the game would most likely be higher when incorporated into classroom curriculum, the designers of the game believe Serious Waste Race would continue to have educational benefits when played outside the classroom. Parents wanting to teach reduce household waste could play the game as a family with their children. In addition to parents, other adults, or environmentally minded students can provide context for other players during the game. Even without scaffolding, the designers of the game believe that meaningful conversations and learning are likely to occur when students play Serious Waste Race on their own.

Ultimately, Serious Waste Race is an educational game with a social activist agenda. With a focus on reducing waste, conserving energy, and shopping smart, Serious Waste Race strives to connect players’ daily actions/choices to their overall environmental impact. The game aims to start conversations about the environmental impact of players’ daily actions/choices and empower them to make real-life changes.

Work Cited:

Gee, J. P. (2007). Good Video Games and Good Learning. Washington DC: Peter Lang.

LeBlanc, M. (2007). Tools for Creating Dramatic Game Dynamics. In K. Salen & Zimmerman (Eds.), The Game Design Reader (p. 438-459). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Koser, R. (2005). A Theory of Fun for Game Design. Scottsdale: Paragylph Press.

Leave a comment